The most important journey we have

is the ‘rest of our life’. To make the

best of it requires good planning. The

best plans have a time frame. They

also show when we expect important

things to occur, why and what we will

do about them. If things change, we

can respond.

Ageing progresses just a

day at a time but there can be sudden

challenges. Without planning, we are

prone to make hasty and inappropriate

decisions

Each of us is different and we tend to

get more different over time. So, we

need our own longevity plan to make

the best of our life and adapt as required.

It underpins our other health, financial, career

and estate plans.

TIME AND LONGEVITY

‘Time’ is the most commonly used

noun in the English language. Most

people understand and speak easily

about time. It makes sense to plan

using time concepts wherever possible.

However, when we come to discuss

‘our time’ – our lifespan – few of us are

well informed. Most of us already know

people are living longer but we don’t

know why and whether it applies to

us. Ignorance can lead to fear, making

us vulnerable to fear-based marketing,

while media comments about old

age, retirement, longevity risk and age

discrimination all add to our anxiety

Yet, we can address this ignorance by

understanding more about longevity

and applying this to create our own

longevity plan. Easy ‘time’ conversations

can enable us to share our thoughts

with others.

WHY HAS COMMUNITY LONGEVITY INCREASED?

So, why are we living longer? Well,

societies generally began to live longer

over the last two centuries

The industrial revolution enabled

communities to develop and fund

infrastructure (such as, sewers, fresh

water, roads and bridges), broaden

and deepen education, and promote

specialist knowledge (as in medicine),

evolve laws and standards, improve

information sharing and so on.

As a result, lifespans in ‘developed’

countries, like Australia, have increased.

Table 1 outlines four time periods.

Not surprisingly, the consequences of

an ageing society, such as increasing

costs and other implications of

this change, are far-reaching. As a

community, we are inadequately

prepared for a wide range of social

issues affecting the funding of age

pensions and superannuation, health

and aged care services, and lifestyle for

older Australians.

This makes it important for us to be

as informed as possible about our

own potential timeframe, allowing us

to better understand the things we

can do to make the most of it and to

integrate this knowledge into our other

planning decisions.

IS COMMUNITY LONGEVITY STILL INCREASING?

Life expectancy has increased on

average by about two years per

decade over the past 200 years and is

currently about 83 years.

However, since 2000, life expectancies

in Australia have declined for people in

their late 80s and beyond. We may be

seeing the end of the ‘easy’ increases.

Increases in obesity in early life may

be one factor: also, as people survive

longer, rising challenges to the brain

and neural systems are difficult to

understand and treat.

This will compound problems for

aged care services and costs, already

increasing and accompanied by quality

challenges. The ethics of prolonging

life is coming under close scrutiny,

with choice of death supported by a

majority of older people.

These are all issues that will influence

the outcomes of personal plans.

BUT WHAT ABOUT ME?

Communities are living longer, but

what about me? There are ‘Life Tables’

that tell us average lifespans for each

age, but the problem is, most people

aren’t average.

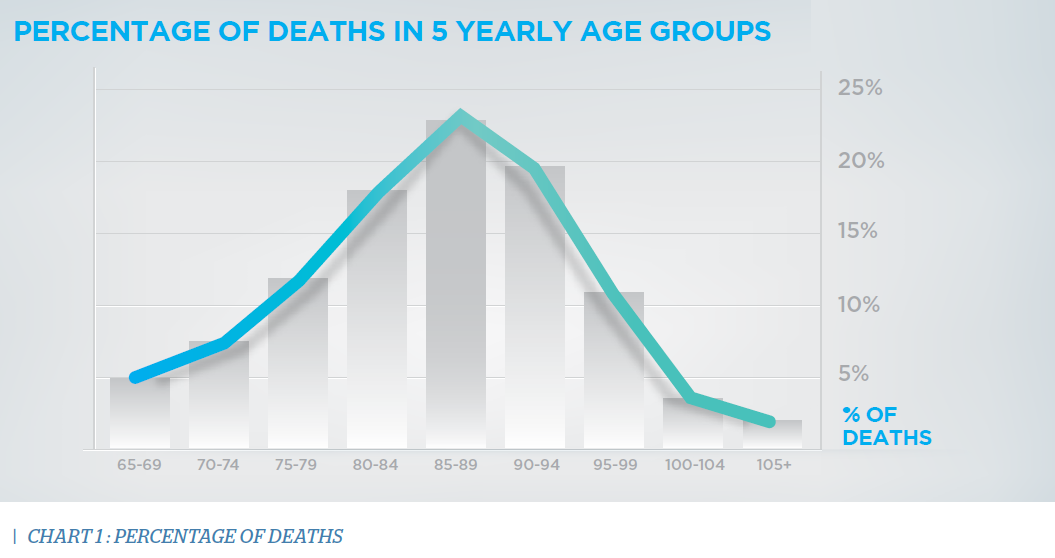

The spread of deaths (in five year

groups) from age 65 shows this. At age

65, less than one-quarter of people live

to within three years of the average

age of 86. The rest are short or long of

the average.

So, what about me? Am I likely to live

longer or shorter than average? It’s

a vital question.

There has been a huge rise in long term studies establishing reliable

links between life expectancies and a

large number of behavioural, health,

social and other factors. More clues

come from the survival data of life

insurance companies.

This has enabled the development of

assessments which give better

indications for individuals. For

example, the SHAPE Analyser is

a free online tool that has been

progressively refined since 2008, providing over

180,000 estimates.

We are no longer reliant on average

data. We can reasonably answer

‘what about me’ and understand why

we might be different from others.

This is allowing us to make better

and more informed decisions about

how we respond to our own – and

our clients’ – longevity.

CAN I CHANGE MY LONGEVITY?

Can I really affect my longevity –

the rest of my life? Or is it just a

consequence of evolution?

Well, evolution plays out slowly

and had little part in the doubling

of lifespans over 200 years. The

industrial revolution was the main

change agent. Communities began to

significantly influence the rest of their

life, and so could individuals.

Time plays out differently at different

ages. When we’re young, shorter term

decisions tend to dominate. By midlife,

priorities are changing.

With increasing longevity, ‘the rest of

my life’ has become more significant.

We can increasingly influence both our

wellness and length of life. Whether

and how we choose to do so, has

consequences for our future health and

funding. Our parents are also living

longer, and we and they are often

poorly prepared for this.

IT’S NOT JUST HOW LONG

The SHAPE Analyser provides a

personal time frame. It also provides

insights into what we could do

to improve our wellness. Further

information is available from the

Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare, which quantifies the average

stages of ‘the rest of life’. See Table 2.

For example, at age 65, on average

there are typically 17 years of living

independently and four dependent

years. We can break down the

independent years to ‘able’ and

‘less able’.

It’s important to note:

- the same things that drive increasing longevity also drive how well we live;

- for many, there’s time to remain well, productive and to get organised;

- we become more different from each other with age: personal decisions do matter;

- the longer we live, the longer we’re likely to live – a survival bonus; and

-

the survival bonus adds independent years and less dependency

(defined as ‘needing support for core daily activities’, and not necessarily for frailty or helplessness).

We can now prioritise our health plans

and other important issues. We can

plan better for potential changes to

our longevity.

MORE ABOUT DEPENDENCY

Table 3 shows the average years of

dependency at key ages. Dependency

tends to reduce with increasing age,

which for many people is unexpected.

Women have almost twice as many

dependent years as men.

However, the greater longevity of

women means dependency typically

begins later. Women are often

younger than their male partners,

who die after a shorter dependency

before their partners enter their

longer dependency. Unfortunately,

women also have a higher likelihood

of dementia.

These are important factors for

financial planning, especially for

aged care, guardianship, powers of

attorney and end of life decisions.

LONGEVITY PLAN

We now have a solid basis for developing a realistic

longevity plan that reflects how long

we may live, why and what we will do

about it, including:

- how we will engage with health advice and take preventative action;

- where we expect to live and why;

- who will manage things – and us – when we can’t;

- who gets what, why (and why not), when and how; and

- our aged care preferences, dependency and end of life.

We can now plan for regular reviews and see how these elements relate to our career plans.

BENEFITS OF A LONGEVITY PLAN

There are many benefits

of having a longevity plan. These

include:

- Each plan is unique for each person;

- It provides a lifetime framework that is easily adapted to changes;

- Immediate and longer-term actions are prioritised, reflecting a client’s life stages;

- It builds relationships and commitment with supportive financial planners and other professional advisers;

- It creates productive interactions with family members and others; and

- It provides a high value.

A CONVERSATION THAT BUILDS TRUST

Most financial decisions have a time

basis, such as how long will my

money last. These decisions can

be based on individual data from a

personal longevity plan.

Time underpins our major

decisions as we age. In fact, a ‘time’

conversation can be easier to have

with clients than a financial one, and

it’s the type of conversation that

builds trust.

By empowering clients to have an

informed and stronger commitment

to their life journey via their longevity

plan, financial planners can take

account of a client’s longevity across

all their key decisions, life stages and

reviews. Longevity planning also

integrates easily with the client

value proposition.

So, isn’t it time longevity planning took

its place in holistic personal advice?

This article first appeared in Money and Life, published in March 2020 by the Financial Planning Association.